Movies

2005: "Not My Blood!"

Three Dancing

Slaves (a.k.a. Le Clan)

Review

by John Demetry

Part III: To BrotherLove

Gael Morel:

Full-Speed Auteur

"Hiphop is about tolerance!" Stephane

Rideau announces in Gael Morel's 1996 Full Speed. In

that film - still

daring - Morel gauges individual's struggle to define

masculinity - while maintaining

ethics and hope in a multiculti, ambisexual (political!) world -

through pop culture. Contrary to critical response (repeated in reviews

of Morel's new Three Dancing Slaves), Morel does not borrow the good

will attached to the Morel-starring Andre Techine-directed Wild Reeds

(a masterpiece in contention for best film of the 1990s). Morel

casts

his Wild Reeds co-stars Rideau and Elodie Bouchez in Full Speed as

contemporary pop icons - whose significance Wild Reeds defined.

Recontextualizing that iconography within a delirious gay-erotic

mise-en-scene (the film opens with a fellatio-frisson blood-brothers

ritual), Morel brings hiphop's full-speed license - and promise of

tolerance - to the big screen. Through Bouchez's uncanny sympathy and

Rideau's buffed and shirtless (with Brando's eyes) sensitivity in Full

Speed, Morel identifies a male delicacy often unaddressed in social

customs and pop culture: Rideau bleeds to death.

Part

2: Christophe: . . . from winter to spring. . .

No wonder Morel stages Rideau's

"resurrection" as Christophe in Part 2 of Three Dancing Slaves as

ritual ceremony. Morel structures the 90-minute narrative of Three

Dancing Slaves (a.k.a. Le Clan) in three parts. Each section is titled

after one of the three brothers who constitute the focus of the film,

as well as identifying the appropriate season of the story's year.  This

second chapter is titled: "Christophe: . . . from winter to spring. .

." While Part 1 is distinguished by the absence of Christophe (and the

brothers' late mother), his return from jail in Part 2 is announced by

a torch entering the frame. The brothers' gang of muscular male friends

celebrates the return of their leader (middle-brother Marc - played by

Nicholas Cazale - asks Christophe to assist him in an act of vengeance

as if he were addressing The Godfather). The clan drink and dance

around a campfire (typifying the intensity of the - HOT!!! -

rock-n-cock montages of male behavior), highlighted by the camaraderie

of Christophe and Hicham (Salim Kechoiuche), the brothers' friend of

Northern African decent.

This

second chapter is titled: "Christophe: . . . from winter to spring. .

." While Part 1 is distinguished by the absence of Christophe (and the

brothers' late mother), his return from jail in Part 2 is announced by

a torch entering the frame. The brothers' gang of muscular male friends

celebrates the return of their leader (middle-brother Marc - played by

Nicholas Cazale - asks Christophe to assist him in an act of vengeance

as if he were addressing The Godfather). The clan drink and dance

around a campfire (typifying the intensity of the - HOT!!! -

rock-n-cock montages of male behavior), highlighted by the camaraderie

of Christophe and Hicham (Salim Kechoiuche), the brothers' friend of

Northern African decent.

Revelry punctuates revealing

interactions, gauging the self-consciousness - the loss of innocence -

signaled by the return of Christophe. Hicham, sensing the shyness of

youngest brother Olivier (Thomas Dumerchez), follows him when he steals

away from the group and tenderly sticks his fingers in Olivier's throat

to help him vomit. Hicham answers Marc's concerns that Christophe has

changed: "We all change." Marc counters: "You can't understand. It's a

brother thing." Morel's curving camera move attests to the sensual and

racial dynamic. Morel defines the "brothers" by the style of their

movement: Christophe/Rideau walks tall, his movements proud and

deliberate (even when his temper strikes); Marc/Cazale darts in

over-emphatic, self-consciously sexy flashes; Olivier/Dumerchez treads

lightly - somewhat gawkily with his long arms - emanating an inviting

warmth; outsider Hicham/Kechoiuche dances gracefully, seductively

(firing the most swoonderful wink in movie history).

Morel begins a shot of a bonfire

revelation with a tight framing of Olivier cuddled up under the arm of

Christophe who says, "It's good to have my little pink canary back." As

the camera pulls back to reveal Marc and other buddies sitting with

them, Marc cautions Christophe: "Don't say that too loud." The camera

closes back in to frame the three brothers as Marc, whose affinity for

horses (or rodeo?) is established in Part 1, relates the story of

Christophe's (sexually provocative) childhood nickname: "Horseface." It

originates at his traumatic birth: "He didn't want to come out." Marc's

analysis of the effects on the shape of Christophe's head - elongated

like a horse's - of the horseshoe-shaped forceps provides entrance to

the film. Morel evinces a sculptural attention (as in this shot's

lighting by fireside and moving camera) to physiognomy - difference and

desire (the narrative and characterizations seem developed from the

actors' bodies, a sculpture defined by the stone). The shot ends with

youngest brother Olivier pining - "This is like a dream" - as

Christophe ("Horseface") nibbles at his little pink canary's ear.

The piano-to-guitar-charge music

score synchs with the film's thrilling symbolic flights (teasing out

the source of tender emotionalism and culturally-specific vitality).

Morel revels in the film's working-class, male-dominated milieu. He

hones in on an unrecognized - frustrated - spiritual vibrancy. Doing

so, Morel develops a challenging and ecstatic form of cinematic visual

representation and movie narrative. Perhaps no "mainstream" filmmaker

has scrutinized social (economic, racial, national) circumstances - and

consequent rituals - in thrall to the dynamics of male behavior with

such idiosyncratic narrative, visual, and symbolic daring since John

Ford (Hollywood's Visconti). (Though, note, the visceral compositions,

editing, and narrative of Morel do not equal the supremely perfected

technique of Ford and Visconti.) Basking in the erotic effrontery Ford

could not (quite) risk - that's what makes Three Dancing Slaves new -

Morel still shares Ford's outsider melancholia and hope.

Melancholia and hope - the twin

towers of desire - constitute the (sensuously) palpable emotions

evinced by Morel's most disputed/dismissed image. After the party

celebrating Christophe's return, Morel presents an image of the three

brothers - nude - asleep together in bed. The shot is not a tableau.

Morel's camera glides along their intertwined bodies. He begins with

Marc/Cazale's penis, then seeks out Christophe/Rideau in the center of

the embrace. Continuing the single sensuous movement, Morel runs the

camera down the body of Olivier/Demerchez, following his foot off the

bed to reveal the Father (played by Bruno Lochet) facing his sons. The

camera climbs to his half-open eyes (with long, light eye-lashes barely

touching). The explicit eroticism of the shot - the transcendence of

taboo - encapsulates the deepest needs signified by the brothers'

relationship. It's all there, all felt in the physical manifestation of

spiritual desire: the mystery of familial bonds, the loss of the mother

in the family, the hope attached to Christophe's return, the lack of a

father figure to imaginatively reconstruct this broken family of men;

the fallen innocence and consequent shame, the possibility of

experience and transformation. The shot is instigated by the

affectionate touch of Hicham - the outsider - to Christophe's arm in

the previous shot, as they preside over the water-play of their gang.

The desire symbolized by the film's family dynamic is the

source of the social phenomenon it

lyrically scrutinizes. Morel resolves the shot - and dramatizes the

hope - by cutting from the Father to a graphic match of Olivier - also

framed in side-view - as he begins to shave. His brothers bust through

the door, teasing the "little pink canary" for growing up and dousing

him with shaving cream (they make jokes about ejaculation). As a new

erotic zenith in film history, Three Dancing Slaves makes the move from

brother love to BrotherLove. To visualize the beginning of this

process, Morel presents Hicham and Olivier practicing the Brazillian

slave dance - capoeira - in sensitive harmony, a beauty heightened by

the on-high composition representing the p.o.v. of Marc. In response to

the spectacle, Marc looks up to the sky and his nose bleeds - and he

swoons.

"I have a secret," Marc confesses to

older-brother Christophe, as they search for Olivier who runs away

after his older brothers fight (a sign of the failure of Christophe's

return to heal the family's ruptures). Marc relays the story of his

last goodbye to their mother: "I told her softly, 'Mum, we love you.'"

And in telling of her anguish, he reveals his own (Morel isolates his

voice by removing the sound of rushing water). After she suddenly awoke

from her coma in response to Marc's  admission: "She grabbed my arm. She

held me so tight. It was as if she wanted to speak. She couldn't

because she was choking. She went like this. . ." Cazele lets loose the

pain of drug-abusing, macho-posing, narcissistic Marc - his facial

features are

admission: "She grabbed my arm. She

held me so tight. It was as if she wanted to speak. She couldn't

because she was choking. She went like this. . ." Cazele lets loose the

pain of drug-abusing, macho-posing, narcissistic Marc - his facial

features are

the most exquisitely feminine of the

three - in imitation of the mother's moans: recognizing in his mother's

stifled expression his own unexpressed anxiety. He exits the frame in

impotent anger at the pain exposed, the sound of the water rushing back

into the soundtrack, and re-enters to beat his fists against the

car

and fall into his brother's arms. Although sustaining a strict

narrative structure, Morel presents each moment as emotional, erotic

aria - these faces, these bodies sing! Some critics mistake this for

porn - eroticism unfettered by conventional plot (or hegemonic

sexuality). If so, it's porn by way of William-Faulkner social insight

and aesthetic ecstacy; in other words: NOT PORN. (As critic Armond

White notes: Morel's character in Wild Reeds writes a paper on Absalom,

Absalom!).

The climactic moments of Part 2 fully

convey the disappointed hope the brothers experience in Christophe's

return: Christophe's capitulation, Marc's self-mutilation, Olivier's

solitariness. Morel symbolizes this schism through an ameliorating

homage. Through the composition of a car's rear-view mirror, Morel

references the key image of desire and difference from the

era's defining work: Steven

Spielberg's A.I. - Artificial Intelligence. Morel utilizes Rideau's

significance to simultaneously engender hope and to make particularly

painful the social containment - prison, work, male roles - of his

special sensitivity (still on view as he attends to the wounds of Marc

- shot as from the p.o.v. of a mirror - after they fight). Christophe -

"Prison taught me control" - gives up the ways of his wild youth only

to succumb to work-place desensitizing. Morel dramatizes his

deliberations: on lunch break, in his car after a humbling shot of the

landscape, and as he opportunistically volunteers for a promotion at a

meat factory. There, Morel cuts the decision with a shot of his

passed-over senior colleague's salt-worn hand ("It's like he doesn't

have hands anymore," as cynically explained/misinterpreted by the

co-worker ironically nicknamed "The Professor"). The body suffers for

displaced feeling. That's the nature of exploitation (note that the

meat factory uniforms - white - leave bodies indistinguishable). Morel

uses symbols of contemporary resonance - the man's salt-bloodied hands,

Rideau's significance, the mother/son moan, the reflection from A.I.,

the taboo-transcending mise-en-scene - to locate and liberate the

spectator's own (exploited)

spiritual essence.

Welcome to

Movies 2005!

Part 1: Marc:

Early in the week, summer. . .

"I want Christophe here with things

like they were before," Olivier prays in his bedroom before the shrine

devoted to the memory of his mother (centered by an urn carrying her

ashes). He is overheard by Marc, who acts as the focus of Part 1,

titled: "Marc: Early in the week, summer. . ." Olivier remains here on

the fringes - his difference defined when he helps his

father on a horse farm, left out of

the work by the other boys. Meanwhile, Marc gallivants with his

weight-lifting, wrestling, beer-drinking, circle-jerk buddies.

Olivier's overheard

confession dramatizes the brothers'

distance and their entwined fates - just as does Olivier's letter to

Christophe in jail - "Everyday is the same. . . same boring routine" -

read on the soundtrack while Marc meanders through the house (Marlon

Brando in Apocalypse Now and "precious bodily fluids" in Dr.

Strangelove embroidered in the abstract soundscape). Thus defining the

desire at the heart of the social vision of Three Dancing Slaves, Morel

gauges the degree to which it fails to be addressed in the explosively

erotic treatment of the film's male cast. Three Dancing Slaves is like

a dream. Morel's visionary proposition on social possibility hinges on

his visualization of untapped, misdirected male sensitivity. He

transforms it into spectacle.

Marc and Olivier, themselves, attempt

this radical transformation by performing a ritual. "She wanted us to

scatter her ashes . . . the sea between France and Algeria. Islam

doesn't allow cremation. That made her happy. She said she was a rebel

until the end," Marc says of their mother as Morel's camera scans the

river into which they will scatter her ashes. Morel shoots the sequence

with momentous power: shifting the focus from the white caps of the

nighttime water to the urn above it, following the sweep of the hand

releasing the ashes. Then he tilts the camera from a view of that water

(rushing to the sea) to an overhead shot of the brothers sitting on the

bridge, where Marc instructs: "This will be our secret" (the secret he

will later confess to Christophe). Later that night, in guilt over

their secret, Olivier has a nightmare and reflexively reaches out his

arm to Marc.

The desire signified by that

unconscious gesture permeates Three Dancing Slaves. Marc, after taking

ecstacy, asks his pet dog: "You're not a dog. What are you inside?"

Confronting that mystery reveals the nature of Morel's ecstatic

approach, just as Marc's query leads him to a particular intimacy with

his dog (they take a bath together). That intimacy bears

emotionally on the section's climax:

an act of euthanasia connected to his torment over his mother, it

reveals Marc's sense of existential impotence. "What are you inside?"

Morel challenges the movie spectator in his presentation of male

behavior in Three Dancing Slaves: working out at the gym, wrestling,

drinking beer on the waterfront, an excursion to Zora's! It is the

question Olivier encounters as he watches Hicham practice capoeira:

isolating the essence of both those who desire and those desired.

Hicham stands unclothed with penis cupped in hand as he watches Marc

have sex with - and then get rebuffed - by Zora (Kheireddine Defdaf), a

boy in girl's lingerie. Then, Hicham propositions Zora by allowing Zora

to remove the restrictive panties, revealing Zora's penis. As Hicham

lowers himself on top of Zora, Morel's camera closes in on a boy

watching.

"What are you inside?" that's the

challenge issued by every significant work of Movies 2005. Morel's

approach to that essential query ranks among the most challenging, the

most

aesthetically advanced - and surely

the most pleasurable.

Part 3: Olivier: A

weekend in early autumn. . .

Morel's cinema taps into - exalts! -

a shared sensual memory of male interaction. Through the cinematic

isolation of that phenomenon, Morel radically identifies a wild space

for personal re-invention and for social/political re-imagining.

"Reaching out" (pace Kate Bush) so far beyond the confines of

conventional identity politics, Morel's revelation can only be

recognized as the definition of "spiritual."

"This is not a love letter": so

begins Hicham's narration in Part 3 (titled: "Olivier: A weekend in

early autumn. . ."). The Faulkner-like device of the not-a-love-letter

narration verifies Morel's genius. Establishing the film's point of

view as that of outsider Hicham, Morel distinguishes the points of

"difference" that map out the three brothers' (and the spectator's)

"wild

"This is not a love letter": so

begins Hicham's narration in Part 3 (titled: "Olivier: A weekend in

early autumn. . ."). The Faulkner-like device of the not-a-love-letter

narration verifies Morel's genius. Establishing the film's point of

view as that of outsider Hicham, Morel distinguishes the points of

"difference" that map out the three brothers' (and the spectator's)

"wild

space." Consequently, every moment in

Part 3 makes intensely palpable Hicham and Olivier's transformations:

1) the sensual memory of male interaction, 2) the extension of that

shared experience into romantic/sexual love, 3) the expansion of that

love - and consequent heartbreak - into each character's distinct

identity, suggesting new social possibility.

"Want me to shave your ass?" Hicham

proposes to Olivier as a form of foreplay. This come-on makes

particular - yet recognizable - the intimacy shared by Olivier and

Hicham - literalizing Morel's blood-brothers trope. This, in contrast

to the isolated narcissism of Marc, whose father catches him trimming

his pubes in front of a mirror (also linked to the head-shaving that

opens the film, Olivier's shaving as sign of maturity, and Olivier

walking in on Christophe - now distanced - shaving after receiving a

promotion). In another dramatization of their intimacy Hicham and

Olivier flirtatiously name the body parts they would eat if they were

ever stranded. In doing so, they (playfully, erotically) recognize

physical attraction and intimacy as spiritual sustenance. In the

narration, Hicham expresses his longing for Olivier: "Nothing lasts

except for the memory of your face." Through that longing - specified

in the "memory of your face" - is bourne Olivier and Hicham's separate

paths of compassion. Evincing that compassion: Olivier's sacrifice to

take care of Marc; Hicham's understanding of the three brothers and new

understanding of the racially stratified gay community into which he

ventures. Asked to identify Olivier in a photograph, Hicham reveals in

the letter his response: "I told him, 'My brother.'" Narrated with

Hicham's expression of longing, the shot of Hicham and Olivier engaged

in capoeira synchs with the look of encouragement Olivier offers Marc

during his physiotherapy (a brotherly extension of Christophe's

girlfriend's expression of sympathy in one of the film's many primal

dining-table exchanges). Through romantic heartbreak, Hicham and

Olivier persevere through and share an essential - primal - heartbreak,

experiencing its rebirth as compassion.

Concluding his letter, Hicham bridges

the gap, from desire to sexual intimacy to compassion to imaginative

engagement: "I know you inside out. I know you and your brothers. I can

tell your tale." It is the essence of heartbreak. Hicham tells the tale

of anyone reading this (Love) "Letter From New York."

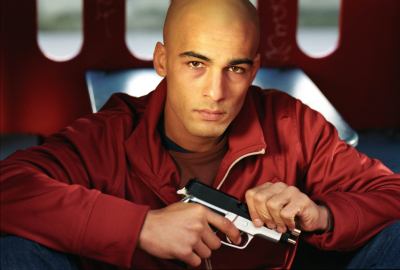

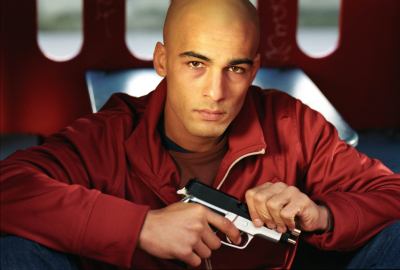

Pictures:

from the top:

all from LE CLAN aka Three Dancing Slaves aka Brüderliebe

(Pro-Fun Media)

zurück

This

second chapter is titled: "Christophe: . . . from winter to spring. .

." While Part 1 is distinguished by the absence of Christophe (and the

brothers' late mother), his return from jail in Part 2 is announced by

a torch entering the frame. The brothers' gang of muscular male friends

celebrates the return of their leader (middle-brother Marc - played by

Nicholas Cazale - asks Christophe to assist him in an act of vengeance

as if he were addressing The Godfather). The clan drink and dance

around a campfire (typifying the intensity of the - HOT!!! -

rock-n-cock montages of male behavior), highlighted by the camaraderie

of Christophe and Hicham (Salim Kechoiuche), the brothers' friend of

Northern African decent.

This

second chapter is titled: "Christophe: . . . from winter to spring. .

." While Part 1 is distinguished by the absence of Christophe (and the

brothers' late mother), his return from jail in Part 2 is announced by

a torch entering the frame. The brothers' gang of muscular male friends

celebrates the return of their leader (middle-brother Marc - played by

Nicholas Cazale - asks Christophe to assist him in an act of vengeance

as if he were addressing The Godfather). The clan drink and dance

around a campfire (typifying the intensity of the - HOT!!! -

rock-n-cock montages of male behavior), highlighted by the camaraderie

of Christophe and Hicham (Salim Kechoiuche), the brothers' friend of

Northern African decent. admission: "She grabbed my arm. She

held me so tight. It was as if she wanted to speak. She couldn't

because she was choking. She went like this. . ." Cazele lets loose the

pain of drug-abusing, macho-posing, narcissistic Marc - his facial

features are

admission: "She grabbed my arm. She

held me so tight. It was as if she wanted to speak. She couldn't

because she was choking. She went like this. . ." Cazele lets loose the

pain of drug-abusing, macho-posing, narcissistic Marc - his facial

features are  "This is not a love letter": so

begins Hicham's narration in Part 3 (titled: "Olivier: A weekend in

early autumn. . ."). The Faulkner-like device of the not-a-love-letter

narration verifies Morel's genius. Establishing the film's point of

view as that of outsider Hicham, Morel distinguishes the points of

"difference" that map out the three brothers' (and the spectator's)

"wild

"This is not a love letter": so

begins Hicham's narration in Part 3 (titled: "Olivier: A weekend in

early autumn. . ."). The Faulkner-like device of the not-a-love-letter

narration verifies Morel's genius. Establishing the film's point of

view as that of outsider Hicham, Morel distinguishes the points of

"difference" that map out the three brothers' (and the spectator's)

"wild