Part II: Just Can't Say

Goodbye

***Liner Notes***

Movie audiences must wait until the release of Gael Morel's Three Dancing Slaves (a.k.a. Le Clan) - review: coming - to enjoy a film that achieves the wild spectacle of masculine delicacy present in the best Billy Mackenzie songs. They certainly will not by attending Gus Van Sant's Last Days ode to Nirvana lead Kurt Cobain. It is revealing, then, that the culture ordains Cobain an icon while the legacy of Mackenzie, front man of the New Wave 1980s group Associates and solo artist in the 1990s, remains in relative sub-cult obscurity. Both singers killed themselves (Cobain in 1994 - the year of Pulp Fiction, Mackenzie in 1997 - the year of Happy Together). Their deaths - like their music - signify something different. Cobain represents the pain that engenders solipsism - a culture that closes itself off from the world made up of people that close themselves off from each other. Mackenzie achieved sublime sensitivity - suffering the pain, then restlessly reaching out to new expression and to boundless compassion. I offer an expanded analysis (B-Side: Re-Mix) of Mackenzie's Associates song "Just Can't Say Goodbye" as a testament to pop truth in the face of hegemony, dismantled in the following review (A-Side: Gus Van Sant's Last Days). Both tracks spin on the turntable axis of the culture's broken heart.

Get ready to groove on the flipside!

***A-Side: Gus Van Sant's Last Days***

Van Sant's Last Days epitomizes the evil of banality. Through the character of Blake (played by Michael Pitt), a long-haired blond grunge rocker, Van Sant invents the circumstances of the last three days of Kurt Cobain - to whom the film pays its debt (twice!) in the fina l credits. Van

Sant sets Last Days at the secluded retreat of the rock star. Disturbed

by drugs and mental illness, Blake wanders through the woods mumbling,

skinny-dipping, and croaking "Home on the Range." Back at the house,

Blake also plays some music and makes bowls of cereal and maccaroni and

cheese. Mostly, he passes out. He also spends some time avoiding or

being avoided by a gaggle of drug-addled groupies and hangers-on: Scott

Green, Nicole Vicius, and Asia Argento and Lukas Haas, who wear

identical haircuts and thick-rimmed glasses. The groupies cavort and

make out with each other. They party and sing along to Lou Reed. During

these three days, there are also some visitors: a black Yellow Pages

salesman who doesn't recognize grunge superstar Blake, a music producer

offering wisdom ending in ellipses ("If you stay here, you'll just. .

."), a detective hired by Blake's wife (never seen), and evangelizing

Mormons. Before he kills himself, Blake escapes to a backwoods rock

venue. He doesn't seem to have a good time. Van Sant's Last Days is

like a movie version of Tori Amos' cover of "Smells Like Teen Spirit."

l credits. Van

Sant sets Last Days at the secluded retreat of the rock star. Disturbed

by drugs and mental illness, Blake wanders through the woods mumbling,

skinny-dipping, and croaking "Home on the Range." Back at the house,

Blake also plays some music and makes bowls of cereal and maccaroni and

cheese. Mostly, he passes out. He also spends some time avoiding or

being avoided by a gaggle of drug-addled groupies and hangers-on: Scott

Green, Nicole Vicius, and Asia Argento and Lukas Haas, who wear

identical haircuts and thick-rimmed glasses. The groupies cavort and

make out with each other. They party and sing along to Lou Reed. During

these three days, there are also some visitors: a black Yellow Pages

salesman who doesn't recognize grunge superstar Blake, a music producer

offering wisdom ending in ellipses ("If you stay here, you'll just. .

."), a detective hired by Blake's wife (never seen), and evangelizing

Mormons. Before he kills himself, Blake escapes to a backwoods rock

venue. He doesn't seem to have a good time. Van Sant's Last Days is

like a movie version of Tori Amos' cover of "Smells Like Teen Spirit."The anti-climax of Last Days presents the release of Blake's spirit from his dead body after it is discovered by a tree trimmer come to do his landscape work. I don't mean this as interpretation: the audience sees Blake's body on the ground and then his spirit - you know it's his spirit because it's translucent and nude - rises from his body and climbs up the window pane in the background. Of course, Van Sant stages the "ascension" to hide Blake's penis, his back turned to the camera. Apparently, this must be clarified: Images NEVER create their own meaning. Van Sant aesthetically moons the audience.

The composition distinguishes the spectator's perspective from the tree trimmer (whose response is never seen). As playwright Ben Kessler observed, the "ascension" of the spirit in Last Days does not occur at the moment of death. In Last Days, transcendence gets triggered by the spectator's gaze. Only the audience is privy (from the same Latin root as "private" and "privilege") to the supposed transcendental moment. Van Sant's idea of transcendence divides between benighted tree trimmer (whose reaction is never shown) and enlightened spectator, between body and soul: normalizing contemporary red-state/blue-state and spiritual binaries at play in the post-9/11 culture. Last Days repeats, in miniature, the years-long spectacle of Kurt Cobain's self-destruction (just as Van Sant appropriated post-Columbine grief with Elephant). Van Sant means to relieve the spectator of guilt, not for the death of a troubled and exploited person (that's just the film's sentimental hook), but for the current divisive cultural climate.

Van Sant reduces Blake/Cobain to a cipher through an aesthetic technique of time-shifts, mannered compositions and bland images, camera moves that follow Pitt or remain independent of his movements, somnambulist performances, and (non-kinetic, unimaginative) tedium. Integrated with the film's non-dramatic episodes, this technique denies the phenomenon of human connection. Van Sant perversely leaves only audience projection on Kurt Cobain - acquiescence to the hegemony amidst the era's spiritual/political crisis - as engagement with the film. "It's a long, lonely journey from death to birth," Blake sings - summing up the film's anti-pop perspective.

Every moment of Last Days represents Van Sant's rejection of the unifying potential of pop art. Here are three examples:

1. The relationship of Haas and Green's characters is never presented as romantic, but just one more element in the groupies' "fluid" sexuality. The two begin to have sex amidst the perpetual drug haze (after planning to abandon Blake). Van Sant later reveals the source of the off-screen music heard during the fumbling (Haas finally takes off those glasses). Blake, alone, performs (the Michael-Pitt-penned) "Death to Birth": sexuality as a "death to birth," rather than the fulfillment of essential innocence through spiritual connection. The time-shifting placement of the static and distanced shot privileges spectator projection.

2. Among the strangers who visit Blake's house: young male Mormon identical twins (Adam and Andy Freberg) evangelizing door-to-door. The twins relate the story, acted as rote (one mouths the speech while the other phonetically repeats it), of Joseph Smith's visionary prayer - the birth of the Mormon faith.

They suffer

the derision of Blake's groupies (and fail to pique Van Sant's sensual

interest). Van Sant crosscuts the Mormon's visit with an

chronologically earlier incident: Blake in a stupor (lowering to his

knees with deliberate deliberateness) while the Boyz II Men video On

Bended Knee plays on the television (its sound warped). This is

followed by a long take of the television as On Bended Knee plays.

Within the long-take context (and ironical counterpoints of the

Mormons' story of and Blake's capitulation), Van Sant attempts to

contain and displace the pleasure of the video's sexual-religious

combination of heartache and romance, rituals of coping and dramatic

pop storytelling. The Boyz II Men On Bended Knee stands in

counter-distinction to Gus Van Sant's Death II Birth.

They suffer

the derision of Blake's groupies (and fail to pique Van Sant's sensual

interest). Van Sant crosscuts the Mormon's visit with an

chronologically earlier incident: Blake in a stupor (lowering to his

knees with deliberate deliberateness) while the Boyz II Men video On

Bended Knee plays on the television (its sound warped). This is

followed by a long take of the television as On Bended Knee plays.

Within the long-take context (and ironical counterpoints of the

Mormons' story of and Blake's capitulation), Van Sant attempts to

contain and displace the pleasure of the video's sexual-religious

combination of heartache and romance, rituals of coping and dramatic

pop storytelling. The Boyz II Men On Bended Knee stands in

counter-distinction to Gus Van Sant's Death II Birth.3. A fan/friend recognizes Blake at a rock show - spotting Blake's discombobulation. Listen closely to what's hidden within the rock-show noise (the film's sound design is far from phenomenological) and the fan's rambling (about Jerry Garcia). The fan offers to Blake a symbol of "virility" as omen of appreciation, assistance. Blake dismisses the offer. Pitt stares off-screen, then crosses out of the shot. In the anti-myth myth-making of the film, surely this is the most symbolic setting. Before his death-to-birth (the definitive gnostic phrase), Blake returns to the social genesis of his career/his expressive mode: the rock concert. The fan's insistence on the validity of the item might, itself, bespeak of the culture's new-age gnosticism, but it also signifies the misdirected desire for truth. By failing to accept that totem of, if not of "virility" then certainly - dramatically - of affection, Blake and Van Sant (through his aural and visual non-presentation) disavow the truth - as social phenomenon - of the spiritual pain that binds the characters.

Van Sant hopes for death to the rebirth of popular culture (the only way his non-art gains acclaim). He bequeaths that death - the film's sensuality-denying, elitist, racist, anti-religious, and anti-democratic biases (the components of Kurt Cobain fixation) - in the film's final moment. Note how Van Sant positions Haas's Luke as the audience stand-in. Luke's glasses reflect the light emanating from the shed in which Blake will kill himself. Luke's hedonism (the film's singular view of sexuality) is matched by his inexpressiveness (he asks Blake - to no avail - for assistance in writing a song addressed to a one night stand). Finally "liberated" (via Blake's faux-spiritual climb) by the very lack of physical-emotional connection shared by the audience in relation to Blake/Cobain, Luke sings a song (in the style of grunge solipsism) in the car by which the groupies escape Blake's final retreat. This directs the spectator to - like the characters - avoid moral scrutiny and political-spiritual reflection. Mirroring the woods through which Blake meandered his way to gnosis, the lenses of Haas' glasses, here, conceal his eyes - an expressive physical attribute. Blake's moon to the audience constitutes the age's key gesture of solipsism, damning the communal experience of film and offering only disengagement to the audience. With Last Days, Van Sant constructs the antithesis of Alex Cox's 1986 Sid and Nancy. In that film's era-defining coda, the spirit of Sid Vicious - along with the spectator - witnesses pop culture's regeneration in the Thatcher/Reagan era from punk to hiphop(e).

As for Van Sant, perhaps only the Sex Pistols (or Jesus) could have mustered enough sympathy: "God, save the queen!"

***B-Side: Re-Mix***

"Now that you've found my letters and read each one out loud": The magisterial "Just Can't Say Goodbye" - a wildly danceable lonesome ballad - from the final Associates album Wild and Lonely significantly opens with this line - referencing Roberta Flack's 1973 "Killing Me Softly." Doing so, Billy Mackenzie extends - thus the adverb: "now" - Flack's erotic dramatization of the dynamic between performer and audience (a relationship Mackenzie called "The Stranger In Your Voice" on the masterpiece 1985 album Perhaps). Released in 1990, "Just Can't Say Goodbye" dropped on the cusp of grunge rock's dominance of pop discourse (which - as with the damaging standard of homophobic, racist rock crix - continues to be prevalent today; see: Last Days). Mackenzie witnesses the dismissal of the strides in 1980s pop - modes of coping through the era's economic/political inequity and the devastations of AIDS - as pending heartbreak. He does so by bringing Flack's explicit performer-audience milieu back to classic pop coding.

An idiosyncratic

rock-and-soul sensibility - drawing upon neglected pop music forms -

distinguished Mackenzie's entire career. By quoting the black female

Flack's recognizable, yet personal, revelation, the white male

Mackenzie announces the influence of marginalized experience and

expression - specifically black and gay sensitivity - on pop culture

evolution. The best pop brings the sounds signifying perseverance and

community to bear on the mass audience's desire for heart-mending and

togetherness. Through his more abstract approach to pop phenomenon on

"Just Can't Say Goodbye," Mackenzie takes on the voice of singer,

listener, and lover: "I've tried everything with you / I need you the

more I do / And I've never felt this way before." He bespeaks (as

spiritual confession, as sexual discovery) a common yearning - a shared

need - after experiencing the promise of Love in popular culture and

intimate relations. Through these lyrics' accompanying female back-up

vocalizations - a melodic moan bearing Mackenzie's and the culture's

torment - Mackenzie encapsulates the pop ritual of one's desires,

fears, and hopes transformed through communal healing: found letters

read out loud.

An idiosyncratic

rock-and-soul sensibility - drawing upon neglected pop music forms -

distinguished Mackenzie's entire career. By quoting the black female

Flack's recognizable, yet personal, revelation, the white male

Mackenzie announces the influence of marginalized experience and

expression - specifically black and gay sensitivity - on pop culture

evolution. The best pop brings the sounds signifying perseverance and

community to bear on the mass audience's desire for heart-mending and

togetherness. Through his more abstract approach to pop phenomenon on

"Just Can't Say Goodbye," Mackenzie takes on the voice of singer,

listener, and lover: "I've tried everything with you / I need you the

more I do / And I've never felt this way before." He bespeaks (as

spiritual confession, as sexual discovery) a common yearning - a shared

need - after experiencing the promise of Love in popular culture and

intimate relations. Through these lyrics' accompanying female back-up

vocalizations - a melodic moan bearing Mackenzie's and the culture's

torment - Mackenzie encapsulates the pop ritual of one's desires,

fears, and hopes transformed through communal healing: found letters

read out loud. Now, comes the profundity.

In love and in pop pleasures, Mackenzie lays bare his soul. "As time stands still before us / I can't say I'm really proud," he defines himself through profound humility: 1) as pop artist accepting the responsibility of giving voice to himself and his audience, 2) as pop audience experiencing self-discovery in the communal realm, and 3) as a person in love - communing with another. Smells like pop spirituality! That is what is under attack in the contemporary culture. Mackenzie responds by exclaiming the spiritual pain caused by encroaching hegemony - "So many have tried to change to me" - and the consequent sublimation of pop catharsis - "These bitter nights are twice as long." Then, he finds existential hope and possibility in the feelings engendered by pop and by Love: "But my angel has proved them wrong."

Mackenzie gauges the culture's lost faith: "But now you won't believe me / You say it's a just a lie." Through the familiar circumstance of intimacy under duress, Mackenzie bemoans the social-political-spiritual ramifications of the lost belief in art and beauty, healing and expression. Challenging hegemony, Mackenzie testifies to faith. He delivers the most emphatic, powerful singing of his octave-cascading career in the second rendition of the refrain: "But how could I deceive me / When I just can't say goodbye." Mackenzie, a Scot, vocally displays the delirious emotional range and special sensitivity of the young Dean Stockwell (to whom he bore a striking resemblance) in Long Day's Journey Into Night, Sons and Lovers, and Compulsion. Yet, on this track, Mackenzie's voice - newly grizzled ("I've ran out of all excuses / I've ran out of cigarettes," he humorously attests to coping) - signifies wearied experience. He brings the full significance (as social testament) of sensitivity and experience to the chorus. It provides the revelation of "Just Can't Say Goodbye": the spiritual stake in communication and social interaction, in language and gestures. Mackenzie recognizes symbolic urgency - spiritual betrayal ("deceive me") - in the act of saying "goodbye" to pop hope. He, thus, transforms the phrase "say goodbye" into an act of righteousness through unbridled vocalization.

The contemporary culture rejects such devastating expressiveness - rooted as it is in political-intimate life knowledge. Mackenzie knew it. With "Just Can't Say Goodbye," he recognizes the risk in sharing pain and admitting humility in the popular realm: "And it hurts me to show these bruises / But please don't be upset." Mackenzie's plea in the second half of that couplet identifies the source of the (undeniable) insensitivity and destructiveness in the culture, rooting out an essential anxiety. Awesomely sung, he responds with compassion by declaring the necessity of healing art. "I'm no good without you darling / I've never had much control," Mackenzie delineates the social - citizenry - values engendered by the revelation of love and art. Mackenzie takes this insight to its spiritual conclusion. Julian (Hounds of Love, Behavior) Mendelsohn's production reflects the communal/cultural support behind - while challenging the listener to dance in sympathy with - Mackenzie's daring confession. The already-momentous drums-strings-keyboard-guitar wall of sound soars along with Mackenzie's voice as he sings: "And I'll need you forever / If I'm to save my soul." This audience-artist, lover-II-lover play on the word "soul" typifies Mackenzie's complex vision. Shaming Last Days out of existence, Mackenzie makes the essential connection between spiritual being and musical/cultural heritage.

His soul is our Soul.

Mackenzie gives form to this truth in the climax of "Just Can't Say Goodbye." Here, Mendelsohn embroiders Mackenzie's voice with the girl-group back-up chorus repeating: "Now that you've found my letters." It traces the historical passage from the moan to pop expression - from bearing witness to the burden to the dream of freedom. Inspired, Mackenzie spikes variations on the refrain with defiance - "Don't make me say it!" - and existential questing - "Why? I just can't say goodbye!" The layers of call and response in the closing of "Just Can't Say Goodbye" conflate the artistic, spiritual, sexual, and political meanings (and sources) of the phenomenon into an ecstatic gestalt - the liberty of postmodern intensity redeemed by the beauty of infinite significance. As proven by Last Days, critics and artists deny this - the foundation of democratic faith - if they just can't say goodbye to the privilege - and hegemonic power structure - symbolized by Kurt Cobain. An oppressive gesture, they say "goodbye" to the pop truth Mackenzie cannot abandon. He responds to the Last Days culture with a final, breathy exclamation that voices Resistance as seduction: "Don't make me!"

Mackenzie achieves pop nirvana.

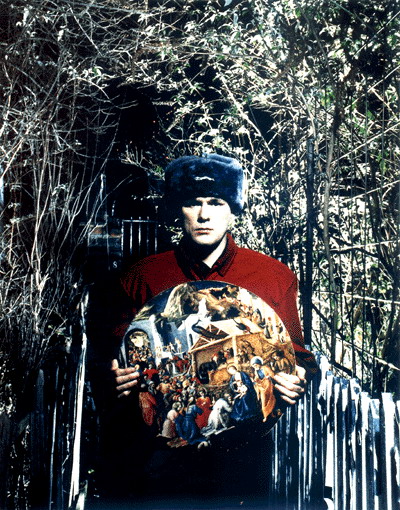

Pictures:

from the top:

Michael Pitt in Last Days (Fine Line Pitures)

Lukas Haas und Nicole Vicius in Last Days (Fine Line Pictures)

Billy Mackenzie

zurück