VERA ICON

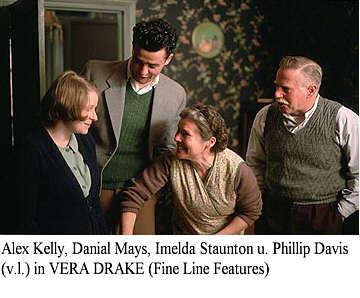

“Vera Drake”

Film Review by John Demetry

Vera = true

Drake = a) a dragon in English

mythology

b) a mayfly used as bait on a fishing line, reminding of the sacrificial lamb and the vocation of the Apostles

c) The name of an English naval hero

who was the first to circumnavigate the globe

“Miracles do happen,” Vera Drake

(Imelda Staunton) attests, cuddling up in the arms of George (Richard Graham),

about their 27-years marriage. This line of dialogue occurs early in Mike

Leigh’s “Vera Drake”. It makes explicit Vera’s (and director Leigh’s)

insistence on the spiritual manifest in social life. Consequently, “Vera Drake”

provides an essential – and emotional – political critique.

Set in the 1950s, a distinctly

post-WWII England, “Vera Drake” details the process and the consequences of

Vera’s side-line role as a black-market abortionist for working-class women

during a time when abortion was illegal in England. The milieu – and genre –

provides an abstracted mise-en-scène to verify certain truths about the role of

government and spirituality in society.

Vera, a cleaning lady for the rich, anchors the film’s various period

environs: her upper-class employers’ homes; her family and neighbors’ company;

the homes of the girls she “helps”; and, finally, the law enforcement,

judiciary, and penal systems (“Mind where you’re going, Drake”,

Vera, a cleaning lady for the rich, anchors the film’s various period

environs: her upper-class employers’ homes; her family and neighbors’ company;

the homes of the girls she “helps”; and, finally, the law enforcement,

judiciary, and penal systems (“Mind where you’re going, Drake”,

instructs/warns a prison guard).

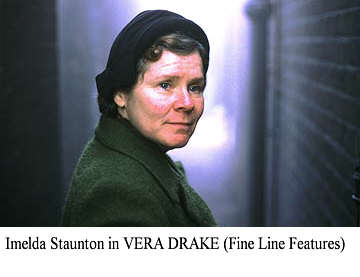

Vera Drake embodies all of the anxieties and the resilience of the culture. An

iconic (see the etymology of her name above) cinematic creation, she manifests

these qualities as a purely benevolent persona (“She’s got a heart of gold,

that woman”).

While cleaning a fireplace, Vera

sympathizes with her preoccupied employer: “Can’t see for looking? I’m like

that too.” Staunton fashions this characterization out of the lost-and-found

verities she perceives in human behavior. She’s at one with Leigh, whose moving

camera seeks out and lingers on the smile that answers a marriage proposal.

Like an essential element in a chemical reaction, Vera Drake puts the

characters and settings – the complex of cultural values in action – into

clarifying relief. Not accepting money for the abortions (“You do it for

nothing?”), but exploited for the gain of her unscrupulous friend Lily (Ruth

Sheen), Vera Drake is Mother

Courage re-imagined as a Sign ‘O’

the Times. Addressing contemporary need, Leigh restores catharsis and

class-consciousness to melodrama.

Leigh uses abortion’s illegal status

in the 1950s as a way of dramatizing the social and psychological – and, yes,

spiritual – damage of an oppressive system: the way laws are enforced to

sustain iniquity and to obstruct happiness. Vera cannot answer the Detective

Inspector Webster’s (Peter Wight) query about when she began performing

abortions. “I’m trying to get to the bottom of things”, admits the detective.

Vera’s inability to respond to the interrogator – this confusion portrayed by

Staunton with the intensity of a soul unmoored – signifies the depths to which

a repressive economic-political system (the 1861 law banning abortion predates

Vera’s birth) infuses all of the characters’ psychology.

Vera’s sister-in-law, Joyce (Heather

Craney), displaces her class anxiety by resting her happiness on the

acquisition of a washing machine, a middle-class status symbol. Consequently,

she begrudges Vera’s investment in family/community rituals. “How can you be so

selfish?” her husband, Frank (Adrian Scarborough), challenges her reticence to

help the family heal by attending Christmas dinner after Vera’s arrest. Joyce’s

lost faith links up with the banal gestures (intolerable cruelties – “You’re

looking very flat-chested”) that restore depressed rich girl Susan’s (Sally

Hawkins) social bearings, signified by her despairingly pleased countenance.

This occurs after Susan’s costly abortion, performed by a real doctor, without

the risks that bring the authority’s scrutiny to Vera’s door. Leigh’s

understanding of spiritual pain as the source and result of social distress

echoes the astonishing moment in Ernst Lubitsch’s “Trouble In Paradise”

(available on Criterion DVD) when

Miriam Hopkins declares, desperately grasping a wad of currency: “This is real!

Money! Cash!” The value she places on the money reveals the actual “real”: her

broken heart.

Vera survives (defines herself)

through faith, recognizing meaning (“Miracles do happen”) in rituals and

symbols. Leigh validates this faith in the movie’s emotional highpoint. Forced

by the police to remove her wedding ring, Vera accedes but protests: “I’ve

never taken it off.” The policewoman (Helen Coker) who instructs her to take

off the ring is sympathetic (synching with the reaction shot in Jonathan

Demme’s “The Manchurian Candidate” showing the recognition of a black woman

present at the interrogation of Denzel Washington’s character), but she cites

“regulations” as the reason for this command. The following series of

alternating close-ups (of Vera’s face overwhelmed by emotion and of her hands

as she slowly removes the ring) communicates the full resonance of this act; it

represents truth under attack by authority. This is real! The emotions elicited

recall a friend’s response to an accusation that Steven Spielberg’s “The

Terminal” is “too sentimental”: “You have feelings, don’t you? Don’t you feel them?”

“Well I don’t think we can allow

that to happen, can we?” a psychiatrist (Allan Corduner) resolves to recommend

that Susan receive an abortion when she threatens suicide as her only other

option. The interaction between psychiatrist and the troubled Susan – a

shrewdly belittling Corduner and a heartbreakingly fragile Hawkins – mirrors

the film’s police interrogations as both kinds of authority figures demand

“truthful” (i.e. reductive) answers – “Were you a virgin? (pause.) Yes” – from

people whose turmoil, the source of their behavior, reaches so deep into their

psyches and the culture that they can’t fully comprehend it, much less express

it. The scene with the psychiatrist ends with a shot of Susan’s face and

transitions to an eye-line-match across space and time to Vera looking on with

compassion at an (as yet) unseen girl in trouble, signifying the healing

compassion that eludes the privileged Susan.

The psychiatric evaluation also

reflects Vera’s court appearances, in which the judge reduces her humanity to

her address (property) and her plea (guilty). Having robbed her of her

humanity, the judge (Jim Broadbent in the house!) then maneuvers to control her

significance, passing full sentence in order to make of her an example, as a

“deterrent to others”. His commanding glance instigates Leigh’s eye-line-match

cut to the journalists in the court-room, all dutifully taking note. In a

devastating dramatization of cultural indoctrination, Vera’s son Sid (Daniel

Mays) calls her “dirty”, influenced by journalistic sensationalism, an

exploitation of benighted imaginations – “You read about it, but you don’t

expect to come home to it!”

Yet! Vera (Icon) also resists.

Intuiting authority’s coercive use of words, she rejects the accusation of

“abortion,” taking a page from the Gospels: “That’s what you call it.” She’s

helping girls out, as she sees it. Even more than Brecht’s “Tragic” heroine,

2000s British Vera Drake recalls the American 1970s television icon Mary

Richards from the “Mary Tyler Moore Show”. This comparison illuminates the

political and sociological understanding Leigh applies to genre. Benevolent

Mary’s grace instigated a weekly (situation) comedy of hope and good will

during the women’s lib era (achieving the perfection of the sitcom form). Now,

Leigh looks back in anger through the post-9/11 lens of global capitalism and

commodified symbols at the forces that converge to contain Vera’s grace –

fulfilling movie melodrama’s potential as contemporary Tragedy.

“Who can turn the world on with her smile?”

In her encounters with the women who require her services – each one a unique

characterization exemplifying the Leigh troop’s rigorous social observation –

Vera assures them: “What you need now is a nice hot cup of tea.” Attempting to

mend the social fabric, Vera delivers this gesture, interpreted by Staunton

with a smile, a nod, and a palpably nurturing intent, her hand clasped around

her wrist held tight under her bosom. At the beginning of the film, Leigh

identifies the social hope signified by this ritual when Vera offers tea to

lonely Reg (Eddie Marsan, this film’s Timothy Spall – is there any greater

praise?).

Vera leaves a young black girl in

despair after suggesting tea. Leigh lingers on the girl (the pain and confusion

Vera cannot assuage). Later, the following exchange takes place regarding the

girl (Lily calls her a “darky”) between Lily and Vera: “What are they doing

over here anyway?” / “Trying to make a life for themselves, I’d imagine.” Leigh

shares the same understanding of social distress and the resulting desire for

healing social rituals as Morrissey, who sings in “Nobody Loves Us”:

“Call us home

Make our tea

Nobody loves us

So we . . . oh . . . we tend to

please ourselves”

Vera offers tea in sympathy to

society’s neglected (pace – bless him! – Reg’s challenge to understand Vera’s

and the women’s transgressions: “If you’re not rich, you can’t love them. Can

you?”). And, so, Leigh offers movie catharsis. In the opening sequences of the

film, Leigh details the rituals of his characters: from the grind of work

(Vera’s daughter manually testing light bulbs!) to modes of release, including

going to the movies. The shot of an audience, a reflection of the spectators

watching “Vera Drake”, moves to a close-up of Vera’s laughter; later, a similar

shot reveals Reg on a date at the movies with Vera’s shy, homely daughter Ethel

(Alex Kelly, who has the piquant vulnerability of Emily Watson).

So important is that release, movies

become part of the vernacular language of the characters in “Vera Drake”, as

when Sid, a tailor, tries to sell a suit by invoking the movie icon of George

Raft. More significantly, the following exchange occurs between characters

discussing the burgeoning love between Reg and Ethel: “I can’t see Reg

dancing.” / “A proper Fred and Ginger, the two of them.” Leigh cuts on this

line to a shot of Reg and Ethel, shoulders slumped, in the park; a humorous

touch, but also just plain touching.

At Christmas dinner, Vera receives a

box of candies and shares them with the guests. She nervously tries to break

the tension (it occurs after her arrest) by having the guests pass the box

around the room, the candies untouched. Leigh’s camera semi-circles the room,

following the box’s journey until it lands in the hands of Reg. Inspired by Vera’s

goodness (Leigh’s hopeful understanding of social interaction), Reg takes a few

pieces of candy. He says: “This is the best Christmas I’ve had in a long time.

Thanks, Vera.”

Miracles do happen. In such moments,

Reg dances like Fred Astaire.